THE WAR YEARS

More About MePhoto: Auschwitz-Birkenau. Photo credit: Memorial and Museum Auschwitz-Birkenau

VPRED MAGAZINE

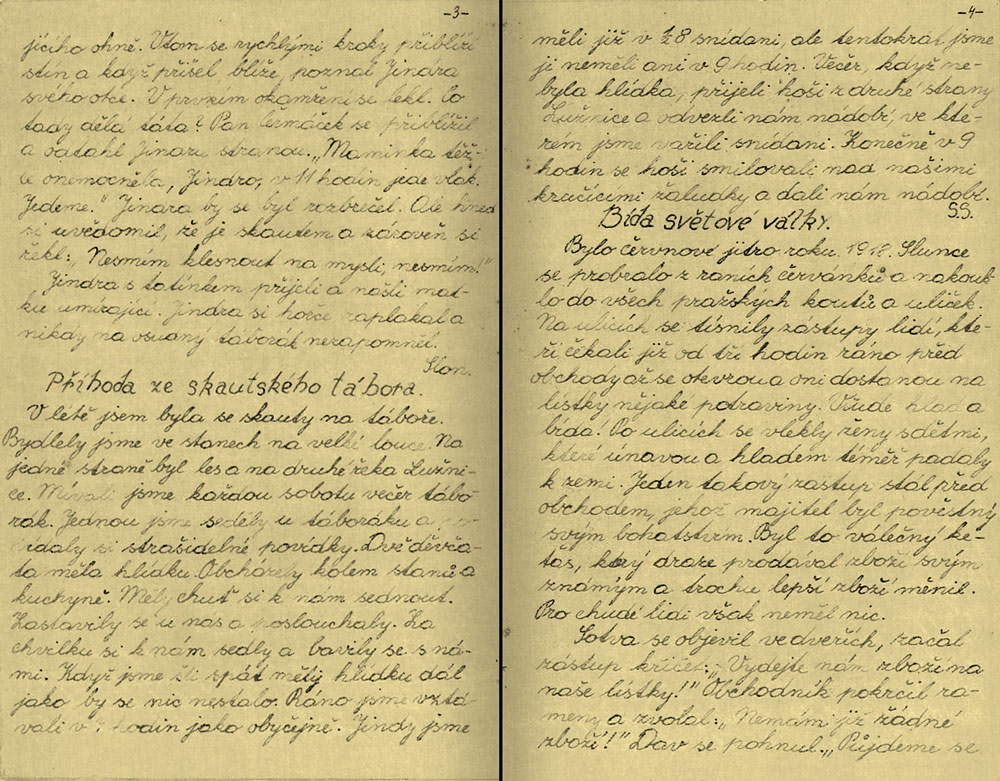

We know very little about the magazines except that the Brady family has a copy of issue 1 & 2, likely the only existing copies. The stories, poetry and cartoons were created by the girls of Room 28 in 1943. Each piece is signed by a code name to protect the author had the Nazis discovered the magazine.

Full issues of editions 1 & 2 include drawings, poetry, prose and comics created by children inmates at Terezin 1942.

VEDEM MAGAZINE

When George arrived at Room 1 - he found a boisterous group of about 40 young boys aged 13-15 grouped together. Their real luck came with the arrival of their ‘overseer’, Valtr Eisinger who pushed a group of troublesome, wild boys to rise above their situation and encouraged them to create an incredible world within the oppressive walls of Terezin.

Valtr Eisinger encouraged these boys to create their own freedom within their imagination. They created ‘Vedem’ (In the Lead) which was a Czech language “magazine” that existed from 1942 to 1944 in Terezin. The magazine was made up of poems, stories, plays, literary reviews, essays and drawings which often described everyday life in the ghetto. It was hand-produced and contributed to by many very talented boys. In particular, it was led by editor-in-chief Petr Ginz and featured many poems by Hanus Hachenburg. The magazine was written, edited, and illustrated entirely by these young boys. Altogether, some 800 pages of Vedem survived the war, while only 15 of the original 100 contributors survived.

George (with other surviving Shkidites) was instrumental in having the book We Are Children Just the Same published in 1995 - a memoir and collection of stories, poetry and prose created by the boys of Home One from 1942 to 1944.

Despite the time that has passed, George still recalled with great fondness when the Shkidites first huddled around on a Friday evening, reading out their secret magazine, beautifully curated and edited by Petr Ginz. George was a contributor, but was admittedly no match for the creativity and pure talent of the boys who contributed regularly. As assistant editor, Kurt Kotouc was in charge of hassling the boys to submit their pieces and articles, and he did so with real dedication. This dedication to the paper and Room 1 did not wane after the last issue was created in 1944.

Kurt would have been most touched by a visit George made in 2010 to the Czech school of educator Frantisek Tichy. Professor Tichy was using the story of Vedem as an example for his students in Prague and George and Lara had the opportunity to see the impact of Vedem firsthand.

“We brought music sheets which we had just found (long thought lost), which accompanied the Shkid anthem in our room. We shared the newly discovered music sheets and under the guise of going to photocopy the sheets for their records, a few students spent 5 minutes trying out the music to the anthem and actually performed the song for us. So the Shkid anthem was sung for the first time since 1944, decades later once again by Czech children. It was incredibly moving and a beautiful way to have Vedem brought back to life.” - George and Lara’s recollections.

Even more heartwarming is how often the Shkidites are honoured by others’ recognition. In addition to his artwork being sent into space, Petr has been immortalized in an official Czech postage stamp, so his face can be shared around the world. In recent years, Hanus Hachenburg has been honoured with productions in France by Claire Audhuy and Baptiste Cogitore.

Vedem Magazine

Various covers of Vedem hand drawn by authors (including the editor Petr Ginz)

Quote from Madeleine Albright:More About Me

I was invited to provide this foreword by George (Jiří) Brady, a survivor of Terezin, a one-time acquaintance of Hanuš Hachenburg, and a fellow contributor to Vedem, the remarkable magazine produced between 1942 and 1944 by boys incarcerated in that ghetto. Mr. Brady’s request was prompted by the inclusion of an excerpt from a Hachenburg poem in my book, Prague Winter, an account of my family’s experiences during the Second World War, including the death of more than two dozen relatives who had been imprisoned at Terezin.

Among the books I read while doing research was We Are Children Just the Same: Vedem, the Secret Magazine by the Boys of Terezin. That volume, overflowing with art, is a work of art itself: a brilliant mix of essays, poems, drawings, interviews and commentary that pulls the reader deeply into a time and place that should never be forgotten. Terezin’s rich intellectual and cultural life -- created against a backdrop of racist persecution, over-crowding, disease, and the ever-present shadow of death -- was the product of many brave hearts and minds. One of the authors was an adolescent, a sickly boy with memorable eyes and a flair for writing. Like all the art of Terezin, the poems of Hanuš Hachenburg cannot be separated from the grim setting in which they were composed, but their quality far transcends mere pathos.

Hachenburg’s use of imagery, breadth of vocabulary, irony, humor, inventiveness, and choice of themes are striking, but most amazing is the charismatic quality of his voice. Reading the poems, we cannot help but wish to embrace and comfort the youthful writer, to engage him in dialogue and probe his thoughts. This was a boy dreaming of his stolen childhood, comparing himself to an unfinished novel, envying the wind-driven flight of the clouds, and picturing himself as a madman shivering with cold, standing and peering “in the window where the heart is partitioned off from the heart.”

Among the more terrifying of his poems is “May,” a narrative that offers images of Spring and then undercuts them so that the “blushing” dawn is accompanied by the sound of a hurricane, the “dew that falls on the field” is seen by the “mocking light”’ of the moon and, when life awakens from its winter sleep, it does so with “arms bloodied and torn with death.” Elsewhere, the poet imagines his heart to be on fire and laments, “I haven’t the strength to put out fire.” Eager for beauty but surrounded by ugliness, he writes in frustration, “I learn to dream.” Exasperated, he asks, “Is the groaning and faith of the night all that remains for me now? Mere faith?!”

All this from a thirteen year old.

The few people who actually knew Hachenburg and survived to tell us about him remember a child who was “odd” and with “his head in the clouds.” From my vantage point across the decades, I imagine a boy acutely self-aware and alive, appreciative of natural beauty, adventurous of mind, yearning with a full heart to love and be loved – in short, a child with ordinary desires but an extraordinary gift for depicting the awful situation in which he had been placed.

In his foreword to We Are Children Just the Same, former Czech President Václav Havel wrote: “The magazine Vedem, produced by children living in Terezin under the constant threat of transport and death…[is] for us who read now, not only a memento of the horrors of the ghetto and of war, but an inspiration to live, and a measure of the pettiness of our present complaints.”

I agree with that assessment; however, it is no contradiction to say that the dominant feeling I have when reading Hachenburg’s poems is rage. Whether Hanuš was executed, starved to death or died of illness is immaterial, the crime is the same, and so is our sadness and anger. Even seventy years later, we cannot ignore the reality that among the millions of atrocities committed by the Nazis was the destruction of the fragile body that housed this unique mind. Certainly, Hanuš was furious at what was being done to him and to his fellows. He was no meek martyr; his sensibility was that of a warrior. In his writing, there are moments of despair, but also notes of a fierce refusal to accept. If his poems have meaning today -- and they do -- it is because of this anger; this fury at injustice; this anguished plea that the world somehow be made right so that a poet would be able to describe springtime without irony and the radiance of a summer’s day without encompassing it in “shackles, bloody shackles.”

The American journalist James Agee wrote that, “In every child who is born, under no matter what circumstances and of no matter what parents, the potentiality of the human race is born again.” The sad corollary is embodied in the fate of Hanuš Hachenburg: every time a life is prematurely snuffed out, the potentiality of the human race is diminished.

We lack the power to turn back the clock or to grant the young boy’s wish (“I want to live”); but we do have the power of remembrance, the ability to learn, and the unrelenting duty – as individuals and as a civilization – to recognize and prevent the resurrection of evil.

Vedem Magazine

THE CAMPS

More About MeTEREZIN

Built in the late 18th century, Terezin was originally intended as a military fortress and garrison. It served this purpose numerous times but was eventually used by the Nazis as a ghetto and prison for the Jews of Czechoslovakia and surrounding countries. Theresienstadt is the German name for Terezin. The fortress consisted of a citadel - small fortress and walled city known as large fortress. In peacetime it held 5,655 soldiers. In the Nazi era, more than 150,000 Jews were sent there including 15,000 children - Jews from CZ, Germany, Austria and hundreds from Netherlands and Denmark. Most prisoners were sent by rail transports to their deaths at Treblinka and Auschwitz, as well as to smaller camps elsewhere. Less than 256 children survived.

Although not an extermination camp, about 33,000 died in the Terezin ghetto. This was due to appalling conditions arising out of extreme population density, malnutrition and disease. About 88,000 inhabitants were deported to Auschwitz and other extermination camps. At the end of 1944, ten more large transports were sent to Auschwitz.

Despite this horror - Terezin was unlike other camps, her prisoners included a plethora of scholars, philosophers, scientists, artists, and musicians of all types, contributing to the camp's cultural life. The Nazis kept a tight rein on the world’s perception of activities within Terezin. In a propaganda effort designed to fool the Western allies, the Nazis publicized the camp for its rich cultural life.

Children’s Homes (Kinderheim) in Terezin:

Most of the children lived in dedicated rooms or Kinderheims separated for boys and girls. The Jewish Council tried to shield the children from the realities of Terezin and tried to ration better food and living conditions for them. Children under the age of 14 often attended secret classes. They had lessons in the morning and physical activity or games in the afternoon. Most of these classes were held in attics with students and teachers keeping watch for guards so that they could quickly pretend to be doing other activities.

- 140,000 people were held prisoner at Terezin from 1942-1945.

- 87,000 people were deported east to death camps, mostly to Auschwitz-Birkenau.

- Of those deported to death camps, 3,600 survived.

- 34,000 died in Terezin primarily from malnutrition, disease and suicide.

- On May 9, 1945, 17,000 people remained in Terezin.

- 15,000 children were sent out east and of those deported to death camps, under the age of 15, less than 300 survived.

Source: Jewish Museum in Prague (home of the Children’s Art Collection of Terezin) & the Terezín Ghetto Museum

More About Me

Terezin Camp

1. Map of Terezin as it existed in 1941-1945

2. Terezin now

RAVENSBRÜCK

Located in northern Germany, close to the village of Ravensbrück, this Nazi concentration camp was created by SS leader Heinrich Himmler in November of 1938. The camp opened in May 1939 and saw over 130,000 female prisoners of whom only 40,000 survived. Hana and George’s mother Marketa was sent here in 1941 and eventually deported to Auschwitz in October 1942 where she was killed. While in Ravenbrück, Marketa was rarely allowed to send letters home. In one of these letters, she included in the envelope a gift for her two children and their cousin Vera. Marketa had made charms out of the only possession she had; her rationed bread.

More About Me

Ravensbrück Camp

Front view of the Ravensbruck Concentration Camp main administrative building.

Attribution: Dolphin and anchor, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons. Source

AUSCHWITZ-BIRKENAU

This notorious camp was the largest of the Nazi concentration camps and was located in occupied Poland, next to the village of Oświęcim.

Of the 1.3 million people sent to Auschwitz, it is estimated that 1.1 million died. The death toll includes 960,000 Jews (865,000 of whom were gassed on arrival), 74,000 ethnic Poles, 21,000 Roma, 15,000 Soviet prisoners of war, and up to 15,000 other Europeans. The majority were killed in gas chambers, using Zyklon B but many others were murdered by slave labour, disease, starvation, supposed ‘medical’ experimentation and execution. Hana and George’s father arrived in Auschwitz on June 11th, 1942 and was killed on July 14th, 1942.

Karel Brady

Intake mugshot of Karel Brady when he was considered a political prisoner and deported to Auschwitz in June 1942 from Iglau Gestapo prison.

The thing I like to do the most and where I'm currently specialized in

I only use the best gear possible to make sure you get the best photographs

Besides making portraits, I also make group photos for companies and friends

Are you a model? Come on by, so we can compose an amazing portfolio together!

Services

.jpg)